The Trouble with Testosterone Supplementation

The Trouble with Testosterone Supplementation

Sidebar: One should definitely NOT assess low T through an online quiz.

Most US males, whether silver foxes or dad bods, will see their testosterone decline with age, dropping around 1-3% per year after the age of 30. Testosterone prescriptions are on the rise (more than a three-fold increase in the last decade), but many questions remain about whether age related declines in testosterone require treatment. Some studies even suggest there are risks associated with testosterone treatment, including increased heart attacks and strokes though there is not yet sufficient data to make a conclusion either way. In the 1990s there was an increase in prescriptions of hormonal replacement therapies for post-menopausal women without long term studies on their efficacy or safety. Post-menopausal hormone replacement therapies were intended to prevent hot flashes and increase bone density but also resulted in increased risk of breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancer for millions of women. When a large, long term study examining the efficacy and safety of menopausal hormone replacement studies was finally conducted (The Women’s Health Initiative), it was halted prematurely because of high rates of breast cancer.

What is testosterone? What does it do?

Testosterone is an anabolic steroid, and helps build muscle mass. As Hans and Franz would joke on SNL, testosterone is here to “pump you up.” Testosterone (T) also affects behavior in humans and other animals; elevated T is associated with increased risky, aggressive, or mate-seeking behaviors while inhibiting parenting behavior.

Ok, so testosterone could help weight lifters and athletes–why would doctors be prescribing it to older men?

The vast majority of older men probably are not trying to become body builders, so on the surface prescribing exogenous testosterone (a DEA Schedule III controlled substance) to older men appears puzzling. Some research suggests that men with very low testosterone production are at increased risk of dying. Men with the lowest levels of testosterone are at the highest risk of mortality in several longitudinal studies. But my Pavlovlovian “correlation does not equal causation” response from Stats 101 compels me to unpack “does low T cause death?”

Birds and testosterone and trade-offs… Oh my!

Canary in the Coal Mine, photo by W. Benton in 1913 via Wikimedia Commons

Some of the most influential testosterone research has been conducted in avian model systems (before you cry fowl, the early studies of testosterone production were conducted in chickens). In birds, healthy males in good condition can maintain higher levels of testosterone than sicker males in poor condition. The effects of high testosterone costs calories; building and maintaining extra muscle tissue is expensive, as is fueling aggressive behavior and mating activities. Mate guarding behavior and fighting other males to expand territories takes precious time and energy. An organism has to make sure that testosterone is not writing cheques that the body can’t cash. In many avian species, males have testes that regress at the end of the mating season, dropping testosterone production dramatically. This frees up time and energy that can then be spent on parenting existing offspring as opposed to seeking out new mates, or that can be invested in survival and immune function. This is a classic life-history trade-off. Like any finite resource, calories spent on one activity can’t be allocated to another.

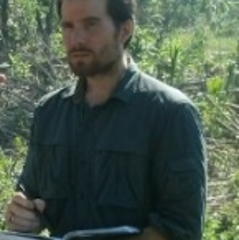

Staying Alive Typically Trumps Reproduction, image by Ben Trumble

Investing in time and energy raising offspring, or invest that time and energy making new offspring- everything has a trade-off. Males who are sick or injured have to allocate their finite caloric resources in immune function and tissue repair, so that energy can’t be invested in muscular development and aggression. As a result, testosterone is decreased so that energy stays focused on immune activation and survival. In this way, testosterone is a bit like a switch. When times are good, invest in bigger muscles or fighting for a larger territory to increase reproductive success. When times are tough, prioritize survival.

Men aren’t birds, but endocrine systems are amazingly conserved among animals. Many of these hormonal pathways are evolutionarily ancient. Among men, naturally occurring decreases in Testosterone happen during the transitions to marriage, and parenthood. And as found in birds, Testosterone regulation in men is sensitive to energy balance and health condition. If a man in the United States fasts for a few days, testosterone drops dramatically. In adult human males, ~20% of resting metabolic rate is dedicated to maintaining muscle tissue. If a man is not getting enough calories to support that muscle, testosterone decreases as the body prioritizes other expensive tissues such as the brain and intestine. Even skipping a single dinner results in significant reductions in testosterone the next morning! Energy balance is not just energy in, it is also energy out, so if a man is burning more calories than he is consuming then testosterone levels go down. US Army Rangers have testosterone levels nearly as low as castrati during peak training when they burn up to 6k calories per day on little food and less sleep.

Army Ranger Training Brigade photo by Staff Sgt. Mikki Sprenkle via Wikimedia Commons

Energy balance- calories in, calories out- not the only part of the equation. Getting sick triggers mobilization of the immune system, which can be quite costly energetically. Almost immediate decreases in testosterone occur with major illness. Minor infections result in decreased testosterone, and even a flu shot is precipitates short-term testosterone decreases.

In short, any time there is an energetic shortfall—not enough food, too much exercise, or illness— there is an immediate decrease in T.

What is a “normal” level of testosterone?

Since testosterone is responsive to environmental conditions, what does this mean for “normal” levels of testosterone? Testosterone levels in the US and other industrial populations are dramatically higher levels than in subsistence populations. For young men the differences are even larger, with studies among Amazonian hunter-gathers and forager-horticulturalists showing levels of testosterone 30-40% lower than age-matched US men. Lower levels of testosterone are reported in subsistence populations around the world, from Bolivia to the Congo, Paraguay, and Nepal.

In industrial populations, we can hunt and gather 20,000 calories at McDonalds without getting out of our car. In the US, infections with parasitic intestinal worms are rare and illnesses are quickly treated by medical professionals. For 99% of human history this was not the case; food security was a constant struggle and parasites and pathogens were commonplace. With low food resources and high parasite load, testosterone is immediately down-regulated so it’s no surprise that nearly every subsistence population examined shows significantly lower levels of testosterone compared to US males. Not only is testosterone significantly lower in younger ages in hunter-gatherers and forager-horticulturalists, but it also appears not to decline as much with age, if at all.

Testosterone levels: Are subsistence populations low or are industrialized populations high?

It’s not that subsistence populations have low testosterone; instead they have calibrated levels of testosterone to the environment they are experiencing. Free of environmental insults and with nearly unlimited calories available, US males can achieve very high levels of testosterone in their early 20s due to their evolutionarily novel environment. Post-industrial life has relieved many energetic trade-offs. We have plenty of easy calories to invest in both immune function and high levels of testosterone, clean water largely free of parasites and pathogens, and illnesses are treated rapidly with antibiotics. All of these factors create a situation where US males can achieve high levels of testosterone at young ages, but could simultaneously create their own risks.

Drawbacks of high testosterone

Beyond the potential behavioral impact of testosterone supplementation on aggression, there are some long-term physiological consequences of high testosterone. Among industrial populations, prostate enlargement in aging men is thought to be a universal; if men live long enough they will suffer from benign prostatic hyperplasia. While not malignant like prostate cancer, 90% of all US men in their 80s suffer from prostate enlargement, which can compress the bladder and urethra resulting in difficult, painful, or frequent urination. The prostate is lined with testosterone receptors, and exposure to testosterone can increase prostate size; the front line treatments for both prostate enlargement and prostate cancer involve medications that reduce circulating testosterone (and other androgens). Indeed studies suggest men with higher levels of testosterone are at higher risk of prostate cancer. Subsistence populations under energetic constraints with low testosterone levels, like rural peasant farmers, and Bolivian forager-horticulturalists show remarkably low levels of prostate enlargement. Even among subsistence populations with lower testosterone, there is still an association between testosterone and prostate size- men with higher T than their peers have larger prostate sizes.

Getting juiced

There are not yet any long-term or large-scale trials in the US examining associations between testosterone supplementation and risk of prostate enlargement or prostate cancer. Studies in animal models suggest that testosterone therapy does increase the risks of prostate cancer. There also appear to be some cardiovascular risks in humans, but systematic long-term, large-scale studies need to be conducted. This means that similarly to post-menopausal women who received hormone replacement therapy in the 1990s, men getting testosterone treatment are effectively a large quasi-experiment, the results of which are yet to be known. Certainly there are reported advantages of testosterone therapy on muscle mass, bone mass density and sexual function, though not in the frequency of sexual activity.

Until we have good long-term data examining the full consequences of Testosterone supplementation, we will not completely know whether these advantages outweigh the risks. And very importantly, a large portion of men getting treatment may not actually qualify for treatment according to American Medical Guidelines- in fact, 25% of men getting testosterone treatment in the US had not ever had their testosterone tested. Worse yet, a recent FDA report indicated that “only about one-half of men taking testosterone therapy had been diagnosed with hypogonadism.” In the UK, testosterone prescriptions increased by approximately 90% between 2000 and 2010, while the diagnoses for clinically low testosterone increased only 1.1%.

Get a juicer

Recent studies suggest that a potentially important source of age-related decline in testosterone is from increases in body fat. When testosterone interacts with fat tissue, it converts into an estrogen, which promotes the deposition of abdominal body fat in men. With higher fat stores there is an increased probability that testosterone will convert to estrogen, creating a feedback loop that can promote obesity. Large-scale studies reveal that men with more body fat show faster decreases in testosterone with age. Studies of weight loss following gastric bypass show testosterone nearly doubled in the two years following surgery. Non-surgical weight loss among previously obese men significantly increases circulating testosterone. So while caloric restriction can result in decreases in testosterone in healthy men with relatively low body fat, decreasing body fat in overweight men can result in significant increases in testosterone. With 74% of adult males in the US considered overweight or obese, men might consider putting down that slice of pizza before picking up a prescription for testosterone.

Photo by Michael Stern via Wikimedia Commons

So who needs testosterone treatment?

Regardless of what an online quiz suggests, only a doctor can decide if you have clinically low testosterone (and guidelines from the Endocrine Society suggest only after repeated blood tests). At the end of the day, it is important to remember that (barring any testicular injury/pathology) low testosterone often means that there is an underlying problem such as illness, obesity, or another inflammatory process. The decrease in testosterone is just a symptom of these underlying issues- like a canary in a coal mine. The body is calibrating testosterone to a level that is appropriate for current circumstances and condition. Circumventing this and adding extra testosterone when the endocrine system is actively trying to downregulate testosterone may be fighting against a body’s own physiology. Testosterone is not a miracle drug or fountain of youth; overriding several hundred million years of vertebrate endocrine evolution may not be the clearest route to better health.

Follow Ben Trumble on twitter @ben_trumble

Further reading:

Sapolsky R. M. 1998. The Trouble with Testosterone: And other essays on the biology of the human predicament. Simon and Schuster. p 147-160.

General:

What Men Really Need to Know About Testosterone Replacement George Divorsky, Gizmodo 2015

Man Up: Is Testosterone an Elixer of Youth? New Scientist 2014 (PayWall)

Testosterone Prescriptions Nearly Triple in Last Decade Rachel Rettner, Live Science 2013

Testosterone Gel Has Modest Benefits for Men, Study Says Gina Kolata, NYT 2016

Scientific literature:

Alvarado, L.C., 2010. Population differences in the testosterone levels of young men are associated with prostate cancer disparities in older men. American Journal of Human Biology 22, 449-455.

Baillargeon, J., Urban, R.J., Ottenbacher, K.J., Pierson, K.S., Goodwin, J.S., 2013. Trends in androgen prescribing in the United States, 2001 to 2011. JAMA Internal Medicine 173, 1465-1466.

Bhasin, S., Cunningham, G.R., Hayes, F.J., Matsumoto, A.M., Snyder, P.J., Swerdloff, R.S., Montori, V.M., 2010. Testosterone Therapy in Men with Androgen Deficiency Syndromes: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 95, 2536-2559.

Bosland, M.C., 2014. Testosterone treatment is a potent tumor promoter for the rat prostate. Endocrinology 155, 4629-4633.

Bouloux, P.M., Legros, J.-J., Elbers, J.M., Geurts, T.P., Kaspers, M.J., Meehan, A.G., Meuleman, E.J., 2013. Effects of oral testosterone undecanoate therapy on bone mineral density and body composition in 322 aging men with symptomatic testosterone deficiency: a 1-year, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. The Aging Male 16, 38-47.

Ellison, P.T., Bribiescas, R.G., Bentley, G.R., Campbell, B.C., Lipson, S.F., Panter-Brick, C., Hill, K., 2002. Population variation in age-related decline in male salivary testosterone. Hum Reprod 17, 3251-3253.

Finkle, W.D., Greenland, S., Ridgeway, G.K., Adams, J.L., Frasco, M.A., Cook, M.B., Fraumeni, J.F., Jr., Hoover, R.N., 2014. Increased Risk of Non-Fatal Myocardial Infarction Following Testosterone Therapy Prescription in Men. PLoS One 9, e85805.

Gan, E.H., Pattman, S., HS Pearce, S., Quinton, R., 2013. A UK epidemic of testosterone prescribing, 2001–2010. Clinical Endocrinology 79, 564-570.

Gates, M.A., Mekary, R.A., Chiu, G.R., Ding, E.L., Wittert, G.A., Araujo, A.B., 2013. Sex Steroid Hormone Levels and Body Composition in Men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 98, 2442-2450.

Gettler, L.T., McDade, T.W., Feranil, A.B., Kuzawa, C.W., 2011. Longitudinal evidence that fatherhood decreases testosterone in human males. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, 16194-16199.

Gray, P.B., Kahlenberg, S.M., Barrett, E.S., Lipson, S.F., Ellison, P.T., 2002. Marriage and fatherhood are associated with lower testosterone in males. Evolution and Human Behavior 23, 193-201.

Gray, P.B., Singh, A.B., Woodhouse, L.J., Storer, T.W., Casaburi, R., Dzekov, J., Dzekov, C., Sinha-Hikim, I., Bhasin, S., 2005. Dose-dependent effects of testosterone on sexual function, mood, and visuospatial cognition in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90, 3838-3846.

Gu, F., 1997. Changes in the prevalence of benign prostatic hyperplasia in China. Chinese medical journal 110, 163-166.

Hammoud, A., Gibson, M., Hunt, S.C., Adams, T.D., Carrell, D.T., Kolotkin, R.L., Meikle, A.W., 2009. Effect of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery on the Sex Steroids and Quality of Life in Obese Men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 94, 1329-1332.

Laughlin, G.A., Barrett-Connor, E., Bergstrom, J., 2008. Low serum testosterone and mortality in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93, 68-75.

McCarthy, M., 2015. US physician group calls for ban on direct to consumer drug advertising. BMJ 351.

Muehlenbein, M.P., Bribiescas, R.G., 2005. Testosterone‐mediated immune functions and male life histories. American Journal of Human Biology 17, 527-558.

Muehlenbein, M.P., Hirschtick, J.L., Bonner, J.Z., Swartz, A.M., 2010. Toward quantifying the usage costs of human immunity: Altered metabolic rates and hormone levels during acute immune activation in men. Am J Hum Biol 22, 546-556.

Nindl, B.C., Barnes, B.R., Alemany, J.A., Frykman, P.N., Shippee, R.L., Friedl, K.E., 2007. Physiological consequences of U.S. Army Ranger training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39, 1380-1387.

Niskanen, L., Laaksonen, D.E., Punnonen, K., Mustajoki, P., Kaukua, J., Rissanen, A., 2004. Changes in sex hormone-binding globulin and testosterone during weight loss and weight maintenance in abdominally obese men with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 6, 208-215.

Orwoll, E.S., 2016. Establishing a Framework — Does Testosterone Supplementation Help Older Men? New England Journal of Medicine 374, 682-683.

Pope, H.G., Jr, Kouri, E.M., Hudson, J.I., 2000. Effects of supraphysiologic doses of testosterone on mood and aggression in normal men: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry 57, 133-140.

Schwartz, L.M., Woloshin, S., 2013. Low “t” as in “template”: How to sell disease. JAMA Internal Medicine 173, 1460-1462.

Shores, M.M., Matsumoto, A.M., Sloan, K.L., Kivlahan, D.R., 2006. Low serum testosterone and mortality in male veterans. Arch Intern Med 166, 1660-1665.

Simmons, Z.L., Roney, J.R., 2009. Androgens and energy allocation: Quasi‐experimental evidence for effects of influenza vaccination on men's testosterone. American Journal of Human Biology 21, 133-135.

Sinha-Hikim, I., Cornford, M., Gaytan, H., Lee, M.L., Bhasin, S., 2006. Effects of Testosterone Supplementation on Skeletal Muscle Fiber Hypertrophy and Satellite Cells in Community-Dwelling Older Men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 91, 3024-3033.

Snyder, P.J., Bhasin, S., Cunningham, G.R., Matsumoto, A.M., Stephens-Shields, A.J., Cauley, J.A., Gill, T.M., Barrett-Connor, E., Swerdloff, R.S., Wang, C., Ensrud, K.E., Lewis, C.E., Farrar, J.T., Cella, D., Rosen, R.C., Pahor, M., Crandall, J.P., Molitch, M.E., Cifelli, D., Dougar, D., Fluharty, L., Resnick, S.M., Storer, T.W., Anton, S., Basaria, S., Diem, S.J., Hou, X., Mohler, E.R.I., Parsons, J.K., Wenger, N.K., Zeldow, B., Landis, J.R., Ellenberg, S.S., 2016. Effects of Testosterone Treatment in Older Men. New England Journal of Medicine 374, 611-624.

Spratt, D., Cox, P., Orav, J., Moloney, J., Bigos, T., 1993. Reproductive axis suppression in acute illness is related to disease severity. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 76, 1548-1554.

Travison, T.G., Araujo, A.B., Kupelian, V., O'Donnell, A.B., McKinlay, J.B., 2007b. The relative contributions of aging, health, and lifestyle factors to serum testosterone decline in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92, 549-555.

Travison, T.G., Araujo, A.B., O'Donnell, A.B., Kupelian, V., McKinlay, J.B., 2007. A population-level decline in serum testosterone levels in American men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92, 196-202.

Trumble, B.C., Brindle, E., Kupsik, M., O'Connor, K.A., 2010. Responsiveness of the reproductive axis to a single missed evening meal in young adult males. Am J Hum Biol 22, 775-781.

Trumble, B.C., Cummings, D., von Rueden, C., O'Connor, K.A., Smith, E.A., Gurven, M., Kaplan, H., 2012. Physical competition increases testosterone among Amazonian forager-horticulturalists: a test of the ‘challenge hypothesis’. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 279, 2907-2912.

Trumble, B.C., Stieglitz, J., Rodriguez, D.E., Linares, E.C., Kaplan, H.S., Gurven, M.D., 2015. Challenging the Inevitability of Prostate Enlargement: Low Levels of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Among Tsimane Forager-Horticulturalists. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, glv051.

Vigen, R., O’Donnell, C.I., Barón, A.E., et al., 2013. Association of testosterone therapy with mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in men with low testosterone levels. JAMA 310, 1829-1836.

Xu, L., Freeman, G., Cowling, B.J., Schooling, C.M., 2013. Testosterone therapy and cardiovascular events among men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. BMC medicine 11, 1.